Category: Republicanism

Republicanism in Britain: A Brief History Parts 1 and 2

1. Introduction

It is ironic that the islands which have produced a disproportionately large number of republican theorists have retained a monarchical system for the majority of its inhabitants. Since the middle years of the last millennium where our story starts, the fortunes of republicans and republicanism can be seen to ebb and flow on centuries long waves.

The two great peaks of republicanism which occurred during the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries were separated by periods where the ideas were held in obeisance. But, as I will show, this is far from saying there was no republican activity during these times. Using history as a predictor of the future is fraught with danger but as the twentieth century fitted into the pattern is is tempting to hope that our present century will witness a new peak.

The Many Facets of Republicanism

Superficially, the history of Republicanism appears to be no more than a straightforward chronicle of anti monarchism in Britain. But such a view overlooks the rich variety of republican thought, some of it only tangentially affecting monarchy.

Indeed, at times writers who considered themselves republicans were quite happy with a monarchy; though one which was tightly constrained, knew its responsibilities and could be held to account. Some of these ideas approach the concepts embodied in the modern office of President of the United States! Likewise it would be impossible to consider the development of British republicanism without reference to wider social, economic and even global events.

Of enormous influence to early British republicans were the ancient Greek and Roman philosophers Aristotle, Demosthenes and Cicero along with historians Livy, Tacitus and Polybius. Similarly, many Reformation English and Scottish republicans looked to more recent ideas flowing from fifteenth and sixteenth century Florence, with Machiavelli proving to be a particularly influential figure.

From the earliest times it is clear that Republicanism is not a single tightly defined concept but rather a loose overlapping collection of ideas and concepts on the nature of citizenship and the exercise of political power. It can also be regarded as a way of thinking or even a vocabulary articulating an approach to political and constitutional issues. At its core is a concern for freedom both for the individual and the state as a whole.

Of importance is the fact that republicanism is most effective and successful when combined with a separate though related cause. In the middle of the seventeenth century this was a lack of religious freedom. Later in the first half of the nineteenth century the driver was economic oppression caused by the rapid growth of unregulated capitalism.

During much of this period the British Isles consisted of three interlinked kingdoms. In fact a United Kingdom of all the islands existed for a very short time in historical terms. The nature of republicanism varied across time and across these countries but in only one, on the island of Ireland has the idea been thus far successful.

Finally, many of the ideas and concepts behind republicanism have remained largely dormant for almost two centuries, being displaced by liberalism and libertarianism as the dominant concepts of freedom. Recovering these buried concepts from past republican theorists demonstrates the great value we have lost in such a concept.t

2. 16th Century Reformation Republicans

Building on the past

It is very rare that ideas and concepts spontaneously arise with no antecedents. So it was with sixteenth century political theory. In England the fifteenth century lawyer Sir John Fortesque argued that monarchical absolutism was a problem for continental Europe rather than England.

Around 1470 he published De Laudibus Legum Anglie which was translated in 1567 by Robert Mulcaster as A Learned Commendation of the Politique Lawes of England. Fortesque followed the Greek philosopher Aristotle in viewing tyranny to br a monarch’s abuse of the property of their subjects with the desire to amass wealth solely for their own benefit at the expense of the people. Similarly, he articulated Thomas Aquinas in declaring:

…the King is gyen for the kingdome, and not the kingdome for the King.

Another Greek thinker, the historian Polybius, was a vitally important source of ideas. He was widely read in late sixteenth century England, influencing the debate by drawing attention to the written constitution of ancient Sparta which guaranteed limits on the power of monarchy. The key institution of the state was the senate which operated effectively because its members ‘were chosen on grounds of merit, and could be relied upon at all times to unanimously take the side of justice.

European humanist works such as Laurentius Grimaldus’s The Counsellor, anonymously translated into English in 1599, endorsed Polybius’s praise of the Roman Republic. Grimaldus argued that the mixed state of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy directly resembled the parts of a man’s mind, making it a natural form of political structure.

Ascending Versus Descending views of Power

Polybius’s works supported an ‘ascending’ view of the balance of power between Crown and Parliament which placed emphasis on the monarch being tied by the laws made in parliament. The rival ‘descending’ view subjugated the authority of representative chambers to the prerogative of the monarch, reducing them to mere advisory bodies.

These two interpretations lay at the heart of political debate of sixteenth century England and recur constantly. But even the ascending view was open to many interpretations with the result that the nature of republican arguments during this time were complex and frequently contradictory.

This dichotomy is clearly visible in Richard Bacon’s 1594 Solon his Foliie, or. Politique Discourse touching the reformation of common-weales conquerred, declined or corrupted. Though dedicated to Elizabeth I it makes extensive reference to both Livy and Machiavelli.

Heavily influenced by the latter, Bacon develops his commonwealth idea by citing examples from ancient Sparta and Athens, the 1579-83 Ulster Desmond Rebellion together with Machiavelli’s own Renaissance Florence. As the court of Elizabeth I sought to protect its prerogative and prevent discussion of the succession during the 1590s, such political treatises were naturally viewed as dangerous.

The Ancient Roman Republic provided a wide ranging and compelling model for sixteenth century political theorists. In his 1568 translation of the first forty books of Polybius’s Universal History, Christopher Warton includes a personal section clearly influenced by Somnium Scipionius., This was an account of the efforts of Scipio Africanus. Scipio, the most talented general of the Third Punic War (149-136BCE), in defending Rome against Hannibal. This raises him to the status of a republican hero.

The Idea of a Commonwealth

A major contribution to English political development was made by Sir Thomas Smith in his De Republican Anglorum; A Discourse on the Commonwealth of England published in 1583. Smith declared:

A Common Wealth is called a society or common doing of a multitude of free men collected together and united by common accord and covenauntes among themselves, for the conservation of themselves as well as in peace as in warre.

Later in the work, Smith articulates one of the fundamental principles of republican philosophy:

And if one man had as some of the old Romanes had (if it be true that is written) v. thousands or x. thousands bondsmen whom he ruled well and though they dwelled all in one citie or were distributed into diverse villages, yet that were no commonwealth; for the bondsman hath no communion with his master, for the wealth of the Lord is onely sought for, and not the profit of the slave or bondsman.

Surprisingly, despite these clear republican statements, Smith is not necessarily an anti-monarchist. Once again it depends on the regal powers being strictly circumscribed by a parliament or other representative body. He does, however, take pains to include even the lowliest sections of society, though as a means of emphasising that the English commonwealth is a collective project.

Drawing a Distinction Between the Office and Person of Monarch

A major impetus to republican theory in England was the heirless state of Elizabeth I. Her chief secretary William Cecil wrote a document which aimed to ‘tackle the potential problem of England without a monarch in December 1592, after Elizabeth suffered a bout of serious illness. It contained a clause which enabled parliament to establish a ‘conciliar interregnum’ and then nominate a successor. This established the all-important distinction between the two bodies of the monarch, the office and the person, in order to preserve the realm in a stable state. This distinction was to prove crucial during the 17th Century.

Cecil’s use of the term interregnum illustrates that following a short period of Parliamentary control, he fully intended that a new monarch should be crowned. This shows that politicians who used republican arguments were often just as repelled by the thought of rebellion as more conservative thinkers. Furthermore it is important to note that republican ideas could be used to preserve as well as attack the monarchy.

Scotland in the Vanguard of Republicanism

Last but not least, a fertile breeding ground for republicanism in the British Isles during the 16th Century Reformation period was Scotland. One of the most influential and original political thinkers. George Buchanan wrote three major works of political theory, De Jure Regni Apud Scotos (1579), Any detectioun of the dunges of Marie Queene of Scots (1571) and Rarum Scoticarum Historia (1582). All were familiar to people south of the border.

My Paper to the Shelley 2017 Conference on Reclaiming His Radical Republicanism

I had the great honour in September to present a paper on the radical republicanism of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and how it influences my political activity. I reproduce it here.

Reclaiming Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Radical Republicanism

1. Introduction

A number of works have analysed Percy Bysshe Shelley’s (PBS) poetry from a proto-left viewpoint (e.g. Paul Foot 1981*). This paper, however, considers the issue of Shelley’s radical political philosophy with specific attention to Republican principles.

Clearly, PBS could have known nothing about socialism or communism. So any analysis based solely on these principles risks misrepresenting fundamental points of his ideology. Viewing his work within a contemporary setting not only brings his political concepts on liberty into focus but reveals a surprisingly strong relevance to current concepts of republicanism. Over the past 40 years researchers such as Quentin Skinner have revealed aspects of republican thinking lost to us for two centuries whilst others have set about the task of evolving them for the 21st Century. When PBS was at the height of his powers liberalism was starting this process of marginalizing republicanism but Thomas Paine and William Godwin, amongst others would have exerted a strong influence on Shelley.

To illustrate the points, the paper focusses on two of Shelley’s poems where the republican vision is most highly developed, Mask of Anarchy and Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things along with the sonnet England in 1819.

2. What is Republicanism?

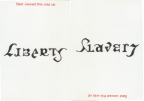

In popular conception Republicanism has become synonymous with anti-Monarchism. But its history and development is vastly richer and it is more accurate to characterise it as ‘anti-Slavery’. The seeds date back over two and a half thousand years when the Roman Republic was established following the defeat of the ruling Tarquin Kings in 509BCE. Indeed our modern word is derived from the Latin res publica meaning ‘public matter or affair’. The early Roman republic bears little similarity to our current idea of Republicanism but we, along with PBS, owe a great debt of gratitude to that great statesman and lawyer Marcus Tullius Cicero (106BCE-43BCE) for codifying the fundamental tenets. Predictably for a society heavily dependent on slavery it was important to define just what a constituted a free person. It is this formulation as an individual free from domination which provides a golden thread right from that era, through Shelley’s time to the present day.

The goal of early Republicanism was to establish the political; system which most effectively liberated citizens to protect their city-state. But around four hundred years ago a significant mutation occurred and republicans began to reformulate the ideas of non-domination explicitly in terms of citizen rights.

So how can we characterise modern republicanism? Professor Stuart White of Jesus College Oxford suggests four overarching principles:

1. Individual freedom defined as not living at the mercy or largesse of another (the famous nondomination doctrine).

2. An economic and social environment promoting and serving the Common Good.

3. Popular sovereignty, appropriately inclusive of all citizens and excluding oligarchic rule.

4, Inclusive and widespread civic participation by citizens.

I shall show how each of these principles are present in the works by PBS under consideration. These ideas were radical in the early eighteenth century and, I argue, are still radical today.

3. Freedom as Non-Domination; Core Republicanism

At the heart of republican philosophy lies a definition of freedom as non-domination or the absence of the condition of slavery. Non-domination is a far stricter doctrine than non-interference which forms the basis of liberal and libertarian ideology. Non-domination asserts that not only must an individual or group be free from arbitrary influence by another, but further, there must be no possibility of such influence. This guards against the benevolent master condition who allows his slaves latitude and possibly wealth, but could change his attitude at any moment. It is in these terms of slavery which PBS grounded his idea of liberty. So in the Mask of Anarchy we find:

What is Freedom? Ye can tell

That which Slavery is too well,

For its very name has grown

To an echo of your own.

The late Paul Foot in The Poetry of Protest asserted that slavery is economic exploitation. For a republican this is a narrow and incomplete view which fails to take into account the myriad other ways which slavery can occur, for example gender oppression which concerned PBS. Again in Mask of Anarchy we find:

‘Tis to be a slave in soul

And to hold no strong control

Over your own wills, but be

All that others make of ye.

4, The economic and social environment

But republicans do agree with socialists that sufficient economic resources are essential to individual freedom. At first, however, republicans took a hardline stance. Cicero, for example, says this in de officiis:

..vulgar are the means of livelihood of all hired workmen whom we pay for mere manual labour, not for artistic skill; for in their case the very wage they receive is a pledge of their slavery.

But as the Industrial Revolution evolved along with the concept of the Free Contract, wage-earning per se was not viewed as slavery in itself but rather the lack of agency to contest the conditions of the contract. This is what concerned PBS and economic hardship is a frequent theme in the works under consideration.

Continue reading “My Paper to the Shelley 2017 Conference on Reclaiming His Radical Republicanism”

The Last Night of the Proms; A Dash of Ancient Feet, Religious Dissent and Republicanism

Opinion over the BBC’s Last Night of the Proms becomes ever more polarised. Increasingly, you either revel the naive jingoism of the second half of the event or it repels you. But I wonder how many of those lauding it as a ‘major cultural treasure’ really know the background of one of its centerpieces, Hubert Parry’s setting of Jerusalem.

The lyrics are from a poem by William Blake, one of the most controversial artists in British history. He was a religious dissenter and no lover of the established Church of England. Like many dissenters he held radical political views and was a republican.

A few weeks ago I blogged about the appalling treatment of Eighteenth and Nineteenth religious dissenters such as the scientist Joseph Priestly by the establishment backed ‘King and Church’ faction. Interestingly, despite religion playing a prominent part in most of his works, Blake was a firm friend of revolutionary thinker Tom Paine.

So what about Jerusalem? The symbolism behind the words is shrouded in considerable mystery and the dark satanic mills are a particular point of contest. They are popularly taken to refer to the oppressive conditions of factories endured by the lower classes during rapid industrialisation. But another interpretation suggests the satanic mills are the Anglican churches and cathedrals, yet another insisting that they represent the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

The published setting for Jerusalem, more correctly known as And Did Those Feet in Ancient Times is an issue rooted in republican history. Written in 1804 the poem is part of a preface to a two volume poetic work called Milton: A Poem in Two Books. The Milton in question is none other than the great republican poet John Milton who was at the height of his powers during the Commonwealth and Protectorate of the 1650s following the English Civil Wars.

So when the Prommers are bursting their lungs to Jerusalem they are indulging in a work with its roots deep in religious dissent and republicanism. Personally, Blake is not the radical I warm to most, with his firebrand advocacy of religion I am more at home with the secular sympathies of Paine.

I would like to think that including the piece in the Proms is an acknowledgement of the importance of dissent to British society. Alas that would be self-delusion and it is likely that the majority of revelers couldn’t care less about the words and are genuinely ignorant of our radical or dissenting past. But they are hardly to blame, living in a culture which promotes a historical narrative of monarchy, privilege and empire and marginalizes the story of the long struggle for rights and freedoms for us all.

Trump, May, and Autocratic Libertarianism – on Bright Green

Click here for my Bright Green article on the origins of the ideology persued by Donald Trump and Theresa May. The roots go back a long way, right back to the 17th Century and present a real danger to our present day freedoms.

Harry Windsor, Contestability and the Problem of ‘Doing Good’

If the Windsors were quoted on the stock market then the past few weeks would have been what the analysts term a ‘rollercoater’ Firstly, Elizabeth Windsor visits the site of the Grenfell Tower disaster and the WinDaq rises rapidly as she is reported as ‘showing Theresa May how sympathy is done’. But then it all spins hopelessly downwards.

In a series of interviews Harry Windsor paints the Royals as victims of a grotesque system ‘enduring’ privilege while not wanting the responsibility which comes with it. In a twist of fate, that argument is actually similar to the one Republicans such as myself deploy, that the archaic monarchy really benefits no-one. So the WinDaq falls. Last week it hit rock bottom as it was revealed that the royals share of the Crown Estates profits will net them a very healthy revenue increase. This is in the same week as the Conservative/DUP deal highlights the dire state of public service funding.

But lets focus on one single moment, courtesy of Harry in an interview reported in the Daily Mail which actually reveals something fundamental. He muses on the point of the yoyals, concluding

‘We don’t want to be just a bunch of celebrities but instead use our role for good.’

It is difficult to see whether this comes from a place of ignorance or naivety. Harry seems blissfully unaware that what is ‘good’ has been the hottset of political hot potatoes for centuries (maybe millennia). He is effectively saying he wants the Windsors to be overtly involved in politics (as if they weren’t already). Straight away there is a problem. For me the monarchy is bad because it represents a fundamental inequality, a secretive and manipulative private interest which distorts the heart of our Government. So ‘good’ for me is a constitutional Head of State accountable to the people.

For centuries the battle lines over what is good has been framed in terms of the balance of individual and state. Libertarians would argue that what is good is few laws and low taxes with a small state since only the people themselves truly know what is best for them. A socialist may argue that what is best is a larger state with higher taxes falling on the wealthiest in order that a redistribution of wealth gives even the poorest a better chance of the good life. There are many other possibilities besides, especially involving the definition of freedom as I have argued elsewhere in my blog. Harry must appreciate he is in a most precarious of positions being afforded a huge level of personal privilege and freedom while being funded by the state. If he doubts this he just need to consider the freedom of action available to people using foodbanks!

It seems the approach Harry wants to take is that of Charles Windsor who pontificates on what is ‘good’ while suppressing debate and dodging accountability. He does this in a number of ways but most commonly by making interviewers sign a 15-page contract effectively handing editorial control to Clarence House. Nowhere is this more focused than on climate change. Charles Windsor calls for allocation of resources to Green projects without the difficulty of saying where those resources will come from who will be the ‘losers’.

If Harry Windsor really wants to ‘do good’ as he says then as the campaign group Republic urges, he must, give up his royal status and argue for what he believes in. But he will find the court of public contestability and accountability a harsher arena than the one to which he is accostomed. Just as it should be!

Republican Inspirations; A Matter For the Heart And the Head

Who knows not that there is a mutual bond of amity and brother-hood between man and man over all the World, neither is it the English Sea that can sever us from that duty and relation…

John Milton; The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (1650)

Inspiration. One of my favourite words implying a positive relationship with a person, event or entity. Among the various definitions of inspiration, this one from from the Merriam-Webster dictionary I find particularly useful:

…the action or power of moving the intellect or emotions

It sums up the dual nature of my enthusiasm for the Good Old Cause of republicanism in its broadest sense, an idea much richer than just anti-monarchism. Let me explain by starting with the emotions.

From Milton to Shelley….

Some writers metaphorically light up my life. One of these is Richard Overton the seventeenth century radical whose pamphlet An Arrow Against All Tyrants changed my life and the way I think about freedom. He was a Leveller and the enduring influence of him and his fellow Levellers can be seen even in the title of my blog. For example, I find this passage very powerful:

I may be but an individual, enjoy my self and my self-propriety and may right myself no more than my self, or presume any further; if I do, I am an encroacher and an invader upon another man’s right — to which I have no right. For by natural birth all men are equally and alike born to like propriety, liberty and freedom…..

Richard Overton ‘An Arrow Against All Tyrants (1646)

Now, there is much in Arrow to feed the intellect, but more about that later. Likewise with the wonderful prose and poetry of Overton’s near contemporary John Milton, an example of which I started this post. Speaking of poets, one has come to embody a sense of defiance and optimism for a better world like no other – Percy Bysshe Shelley (OK, him again for any regular readers of my blog!!). But where did I encounter him? Some time ago I read a post by Cliff James (he can be found on twitter as @cliffjamester), Cliff’s post was centred on Shelley’s radical poetry; of which I confess I was then largely ignorant. II started with England in 1819 a mightily powerful piece of radical writing.

Continue reading “Republican Inspirations; A Matter For the Heart And the Head”

Reclaiming a Positive Idea of Patriotism

Some time ago I came across a wonderful definition of patriotism which defined it as a vibrant celebration of community. I must confess that I cannot recall just who said it; I’m pretty sure he was a poet and if anyone out there is reading this post and can remind ne I’d be very grateful.! I like this definition for many reasons. Firstly it is scalable. Your community can be a tower block or a village, a town, city, region, nation, continent or even conceivably the whole world. Furthermore, this idea of celebrating your community is not exceptional and does not prevent an understanding that other people have a right to celebrate their community. Strong confident communities are less prey to the fears and inadequacies which breeds intolerance These features also make it an inclusive concept as opposed to many ideas of nationalism which so often cast it in an exclusive light, where by necessity a clear distinction is made between one group and another.

But this definition also implies a measure of responsibility, a fact pointed out by one of our great poets, Percy Bysshe Shelley (no surprise for my blog followers!). In his Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things (for more details see my OpenDemocracy article) Shelley uses the words “patriot” and “patriotism” three times. Each time he makes it clear that the duty of a patriot is to attempt to shine a light on the corruption and secrecy that bedevils parts of our society. For example, speaking of Government he says:

And shall no patriot tear the veil away

Which hides these vices from the face of day?

This idea of patriotism is closely related to the idea of English lexicographer and author Julian Barnes who adds a dash of justice and wisdom to Shelley’s sense of virtue.

The greatest patriotism is to tell your country when it is behaving dishonourably, foolishly, viciously.

This harks back to the first definition since strong communities are open and just communities. As a republican I am used to being labelled unpatriotic, as someone who hates Britain or is at best naïve and idiotic. But my sense of patriotism makes me deeply concerned about growing inequality which may fatally weaken our society, along with a ramshackle constitution which endangers all of us whether we realise it or not.

Definitions of patriotism have changed over the centuries, most being evolutions of its root as the middle French word for a countryman. On very many occasions it has been used as a synonyms for nationalism or, worse, jingoism. But I think the spirit is very different and expresses something valuable.

Republicanism and Democracy; Two Ideas Not To Be Confused

Politicians are fond of throwing aeound the word ‘democracy’ as though it is a talisman, warding off tyranny in the same way as a clove of garlic drives back Count Dracula. But it is in fact a tricky and complex concept, as spectacularly demonstrated by the fallout from the Brexit vote. So lets clear up some confusions.

As a republican (in the European sense for any US followers so I’m not thinking of the GOP here) it is important for me to understand the part played by democracy. There are some people who simply equate republicanism with democracy as though they were the same thing, but the situation needs clarification. Lets dispense with the more obvious differences. For example, North Korea styles itself the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Although nominally a republic (just), it is far from democratic and proof that you can call yourself what you like, it is the Constitution which counts! In this case North Korea is an Autocratic Republic Also consider Iran, or the Islamic Republic of Iran, in this case it is a Theocratic Republic. So strictly speaking all Republicans I know are Democratic Republicans. So far, so good.

Now, leaving aside the convoluted and discarded historical theories in which monarchs can actually be part of a republic (such as Rousseau’s idea) we can ask what is the status of democracy in a republic. In fact the Brexit vote illustrates the issues quite well. Consider that the vote told the Government what to do (withdraw from the EU), but did not tell the Government how to do it (how much sovereignty, if any, must we share in any trade deal)! So the role of democracy is as a means of controlling and holding the Republic to account by the people, but it is actually quite poor at what is known as ‘deliberative’ decision making. Furthermore, the idea that democracy enables everyone to have a say in Government is far from clear, as the 48% who voted Remain may possibly have no say at all in the final settlement. By the way, this would also have been true if the 48% had been on the Leave side. This also raises the question of just who participates in the formation of policy in the first place, a point I considered in a post on radical Thomas Rainborough.

This means that a Republic must have some non-democratic elements to rein back a Government pursuing aims for which it actually has no mandate, no matter what it tries to claim. So, for example, we do not know how many UK citizens would be happy to remain inside the Single Market. Assuming all 48% Remainers, we cannot know precisely how many Leavers would be happy to do so, if it retained jobs and educational opportunities. In the UK the justice system can be regarded as part of this non-democratic brake, although it is an imperfect piece of machinery being dependent upon citizens having the resources or sponsorship to bring a case. Also in this category is the totally unsatisfactory House of Lords as I blogged about here.

So we must be careful when using words such as republic and democracy as they are very different concepts and a well regulated Republic will ensure steps are taken to ensure democratic processes do not actually become a tool of oppression. Likewise we must be aware of the unthinking correlation of democracy and direct elections and appreciate the positive role which non-elective means of democracy can play in our brave modern Republic. But I’ll leave that for a future post.

A Sobering Reminder; There Is No Future in England’s Dreaming

God save the queen

She ain’t no human being

And there’s no future

In England’s dreaming.

God Save The Queen – The Sex Pistols.

On Thursday evening I was reminded that sleep and dreaming has been a recurring theme when describing England, more specifically Southern England. The trigger was Republic Birmingham’s second poetry evening. This event contained a twist as it started with a debut standup comedy routine from Pete, a new member of our group. Sadly, due to traffic congestion I missed the first part but the ease with which he took the interruption of my late arrival completely in his stride belied his inexperience. A unique and valuable comedy talent in the making. Then on to the main event, Spike the Poet making a return visit to our evening. Once again he did not disappoint with an intelligent mix of humour, passion and biting comment on the farce of monarchy. Some wonderful anecdotes by way of background to a few of the poems reflected the depth and complexity of human relationships in the modern world. Find out more about Spike on his Facebook page.

My contribution was next and eschewing my beloved Shelley I read a poem (abridged for length) by Chartist Gerald Massey. My choice, Tradition and Progress, written in the mid 19th century, intertwines republicanism and anti-war protest with rage at the poverty experienced by many working people. You can read more about Massey in an earlier post.

So what about the dreaming? The last item was a prose reading by Alex Simpson. He chose the last paragraph of George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia which recounts Orwell’s experience in the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s. In my Orwell readings I had not got around to this book so the tract was fresh and had impact. Having returned to England Orwell despairs of the complacency he perceives, concluding:

Down here it was still the England I had known in my childhood: the railway-cuttings smothered in wild flowers, the deep meadows where the great shining horses browse and meditate, the slow-moving streams bordered by willows, the green bosoms of the elms, the larkspurs in the cottage gardens; and then the huge peaceful wilderness of outer London, the barges on the miry river, the familiar streets, the posters telling of cricket matches and Royal weddings, the men in bowler hats, the pigeons in Trafalgar Square, the red buses, the blue policemen–all sleeping the deep, deep sleep of England, from which I sometimes fear that we shall never wake till we are jerked out of it by the roar of bombs.

From Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell

Orwell and the Sex Pistols are simply two of many, poet Philip Larkin a notable example, who have used sleep and dreaming imagery to describe the state of England. With a ramshackle constitution, increasing intolerance, and a seeming acceptance of ever more authoritarian inclined politicians talking of Empire 2.0 we are still sleeping and dreaming – and jeopardising our future!

Give a wrong time, stop a traffic line

Your future dream has sure been seen through.

Anarchy in the UK – The Sex Pistols